|

If you’ve struggled with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) like Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or microscopic colitis, or if you just have a sensitive gut and deal with uncomfortable symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation, you have likely noticed at least some connection with food and symptoms. This can cause some people to fear food, which is completely understandable! But as a registered dietitian working with individuals with gastrointestinal issues, I have some really important news for you: your gut needs fuel to work properly. It needs to be fed and nourished regularly, and it also needs breaks between meals and snacks to digest food and move it through. The other encouraging piece of news I want to share with you is that some types of food can actually help to alleviate symptoms, rather than worsen them! Some foods, and some ingredients in food, can be triggers for some people; other foods can be soothing and healing. Whenever possible, I love to talk about what to increase than what to decrease or eliminate, so let’s talk about ten of my personal favorite gentle foods for a sensitive, irritated, or inflamed gut.

Looking for more personalized assistance with your gut symptoms? I’m here to help. Feel free to send me a message or schedule an appointment so we can get to the bottom of your issues and get you feeling better. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist with a passion for helping people improve their mental health and gut health using integrative and holistic therapies.

0 Comments

You probably know that sunshine can boost vitamin D levels. But did you know that getting enough sunshine, especially in the morning, can also help with sleep and mental health? It seems simple, but many of our schedules don’t automatically make time for it: a morning walk through the grass in the sunshine, 15 minutes on the patio while eating your breakfast, or even (for those who live in areas where it’s frequently still dark or cloudy in the morning) using an indoor UV sun-mimicking lamp. Now that it’s wintertime, it’s even more challenging for many who live in cold and cloudy climates to get the sunshine their bodies need. Sunrise, sunset Yes, sunshine is our primary natural “source” of vitamin D. (The UV-B rays of the sun actually activate a complicated chain of events in the skin that causes our bodies to produce vitamin D. While you make the most vitamin D when you’re outside when the sun is highest in the sky, early morning sunshine is considered the best for skin health, including reducing the risk of the damage that can lead to sunburn and skin cancer.) But getting out in the early morning rays is about more than just vitamin D production. And conversely, those recommendations to avoid artificial light and especially screens late at night is about more than just melatonin production (though that is hugely important). Our bodies and minds are made to operate on a “clock,” meaning that we operate on 24-hour cycles that are set by exposure to the cycle of day and night, sunshine and darkness. Here are a few of the systems and tissues in the body that function on a circadian rhythm—many of them even independently from the brain and central nervous system:

How does this apply to mental health? I think we’ve established that our bodies operate in a rhythm, a daily 24-hour cycle that is fueled by the sunlight. So what does this have to do with our mental health? The connection between sleep disturbance, circadian rhythm dysfunction, and depression is well-established. Sometimes sleep disturbances happen as a result of mental illness; other times they may cause it, and perhaps most of the time, it’s going both ways. People with major depressive disorder have different body rhythms than people who don’t have the diagnosis. For example, our body temperature changes on a 24-hour cycle, with lower core temperatures at night. For someone with MDD, their body temperature doesn’t decrease as much. Their melatonin and cortisol levels don’t change as much in the course of the day, so they might not produce enough melatonin for quality sleep or enough cortisol to get through the activities of the day. The degree of misalignment between the internal clock and the timing of actually being able to fall asleep seems to correlate with the degree of severity of symptoms of depression. Plus, there’s all sorts of other impacts that sleep disturbance can have on mental health. Insomnia increases levels of inflammation in the body, which (as we’ve discussed in other posts) can be correlated with depressive disorders. In the long term, sleep deprivation can also decrease the production of some really important brain proteins that support brain growth, elasticity, and resilience. There’s even a weakening of the blood-brain barrier, the “wall” that keeps stuff from the rest of the body away from the fragile tissue of the brain. This can let in all kinds of neurotoxic substances, leading to more inflammation. Others dealing with depression may have the opposite experience, where rather than insomnia, they find themselves sleeping too much. This is also potentially linked to circadian rhythm dysfunction, imbalance of melatonin and cortisol, and poor-quality sleep (which is very common in depressive disorders). So what can we do about it? Nothing in biology is ever quite as simple as the word “reset” makes it sound. Recalibrating or resynchronizing your body’s clocks is not as quick and easy as resetting your Wi-Fi router. But there are some fairly simple steps we can take to try to get back on track, improve our sleep, and improve our mental health. Many of these tips won’t be new to you, but hopefully you now have a deeper appreciation for their importance, and for specifically how they might improve not just your sleep, but pretty much everything else that happens in your body, as well.

Remember: it's all about starting small, incremental, gentle. Be kind to yourself. Choose one thing you can do today. Notice how little changes can have big impacts, especially when they are done mindfully and with self-compassion. Sources:

Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPIntegrative and functional registered dietitian nutritionist.

One of the goals of mindful eating is developing an increased awareness of sensations within the body, including knowing when one is “hungry” and when one is “full.” But while this may sound simple, hunger and fullness can actually be a lot more challenging to identify.

That’s partly because hunger is not binary. Meaning, it’s not just either-or: either hungry, or full. Hunger and fullness exist on a continuum. Often, figuring out where exactly we are on that continuum takes more attention than we tend to pay to anything going on internally. In the process of learning to tell when to start and when to stop eating, it can be helpful to put numbers on that continuum. While the sensations of hunger and fullness aren’t the same for every person, here’s an example of what that might look like on a one-to-ten scale: 1 – Starving! I have severe hunger pangs and feel shaky and weak. I am obsessing over food. 2 – Ravenous. I am really hungry, but it’s not yet intolerable. I am thinking about food constantly. 3 – Hungry. I have slight hunger pains, but it’s not uncomfortable. I know what I could eat and feel satisfied. 4 – Mild hunger. My stomach is growling, I know I will want to eat soon. 5 – Neutral. Not hungry, not full. 6 – Mild fullness. I am filling up, but I could eat a bit more to feel totally satisfied. I feel energized by what I have eaten. 7 – Full. I am totally satisfied and feel no hunger. My energy level has been topped off and I feel like I won’t be hungry for hours. 8 – Slightly overfull. I should have stopped eating a few bites ago. Stomach feels a bit swollen. 9 – Overfull. I am overfull and bloated, uncomfortable and sleepy. 10 – Stuffed. I am full to the point of feeling stuffed. Extremely uncomfortable. I have eaten much more than what was good for my body. I have no energy. I feel like I could be physically ill to relieve the discomfort. (source: whatsforeats.com.au) On the scale above, you would probably want to keep yourself between a 3 and a 7 most of the time. While there are always going to be exceptions in either direction—it’s a totally normal part of normal eating to sometimes be a bit too hungry and sometimes be a bit too full—our body and mind tend to work best within that comfortable zone between the extremes. Getting below a 2 or 3 on the hunger scale can make it difficult to focus on other tasks and can lead to overeating when you do eat. It may make it difficult for some people to get enough energy and nutrients over the course of a day. It may also lead to slower thinking and decision-making and cause you to not move your body as much. The bottom line: there is a reason why our bodies tell us that we are hungry, and it’s important to our health that we listen. Routinely eating past a 7 or 8 is uncomfortable and, for some people, can lead to stomach and digestive problems (such as acid reflux or diarrhea). The feeling of fullness often does increase slightly over a few minutes after you’ve finished eating, which is why slowing down the process of eating can be helpful if you tend to be a quick eater. The bottom line: if you’re routinely eating past fullness, stop and ask yourself why. Is there another reason besides hunger that you’re eating? (This is not necessarily a bad thing, but helpful to be aware of.) Are you eating too fast? Do you set your fork down, chew thoroughly and taste your food, take sips of water, and take the time to smile? Are you always in a rush, eating on the go, or anxious about the food you’re eating or the environment in which you’re eating? Try stopping yourself routinely throughout a meal to think, how hungry am I? If I stopped now, would I have the energy I needed to be active and stay focused for the next few hours? If I took a few more bites, would I feel better, or worse? As a mindfulness practice, you may want to try to figure out your just-noticeable-difference—the number of bites it takes to make a discernible difference in your level of hunger/fullness. Above all, don’t let mindful eating become stressful or make your mealtime less enjoyable. Use it to help you get the most out of your meals and snacks, enjoying them to the fullest and ensuring that they give you energy to live your life and feel well. Note: Mindful eating can be very helpful for some, but not for all. There are several groups of people for whom I tend to avoid recommending mindful eating, at least early on in our work together. For example, if you are dealing with disordered eating that leads you to feel very anxious about food, you may need to start with a more structured approach towards eating rather than with mindfulness in the initial stages of treatment. Additionally, some patients with functional bowel disorders may deal with an excessive focus on internal sensations (this is known as visceral hypersensitivity) and trying to increase focus on the sensations of hunger and fullness may not be appropriate initially. If you’re wondering whether practicing eating mindfully would be helpful for you, I encourage you to talk to a dietitian or counselor. If food is of particular concern, try starting out with practicing mindfulness in other areas of life first—mindful movement or mindful walking might be a lovely place to start.  I've been quiet on my website for a few months taking care of my new baby girl. It's hard to believe how much she's grown and changed in the past 6 months. She's amazing, she's beautiful, she's everything. It's been a busy time, but having a daughter has helped spur me to think even more deeply about the world I want her to grow up in, and how I can be a part of building it. This one's for the clinicians out there. Let me tell you something that I think is vital for all of us to know. Whether or not you work in the mental health space, like I do, you work with clients with mental health concerns. You work with clients with trauma. We all do. Trauma is so unfortunately common that it's impossible not to. We all want to do right by our patients, and truly help them. But have you ever been in an appointment with a medical professional where you felt uncomfortable? Where you felt they didn't understand your emotional and psychological needs? Have you ever experienced a physical exam where you felt you were not being touched appropriately? Ever felt like terms were used that were either too medical-ized or too personal? It's unfortunate, but it is true: re-traumatization happens often in healthcare. We want to be part of the solution, but if we're not careful, we can be part of the problem. And there is precious little training available to dietitians and nutritionists who want to grow in this area. I want to build a world where everyone in healthcare is knowledgeable about trauma and prepared to treat every patient in a trauma-informed way. I've started teaching and doing trainings on trauma-informed care to try to fill this gap. I'm working on creating content and courses for providers to help you build your skills, so be on the lookout for more content, including:

How can I help support you in learning about trauma-informed care? Let me know in the comments below or feel free to send me an email at ericagoldennutrition@gmail.com.

Magnesium is one of my "all-star" nutrients for both gut health and mental health. Today, let's talk all things magnesium - why I love it, and when and how I recommend my patients use it!

What does magnesium do? Magnesium is an essential mineral, and it is important for a bunch of different systems and functions in the body:

What causes magnesium deficiency? Magnesium deficiency or insufficiency is unfortunately pretty common, considering all the important roles it plays in the body. Low magnesium levels can be caused by:

How is magnesium involved in anxiety and depression? Magnesium is intricately involved in mental health. Low magnesium levels are linked to increased inflammation, circadian rhythm dysfunction (i.e., sleep issues), and poor tolerance to stress. We have discussed in previous posts the connection between inflammation and depression. Poor sleep is often a factor in worsening mental health, as well. Plus, magnesium is involved in balancing neurotransmitter function to promote CALM. How can I get enough magnesium? There are lots of dietary sources of magnesium, but they are mostly whole foods - which unfortunately are under-consumed by most Americans! Green leafy vegetables, whole grains, fish, nuts, and seeds are all great sources. When foods are processed and refined, magnesium content is sometimes lost, and Americans tend to eat a lot of processed and refined foods, which may partially explain why rates of deficiency and insufficiency are so high. We get varied levels of magnesium from drinking water, depending on the source (mineral water and well water tend to be higher, but exact levels vary). The Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for magnesium is 310-320 mg/day for women and 400-420 mg/day for men. (For reference, one of the highest-magnesium foods is pumpkin seeds, which contain 168 mg magnesium per ounce. Most other nuts, seeds, whole grains, and beans contain more like 30-60 mg per servings.) If you're concerned you might not be getting enough, or you want to see whether additional magnesium might help some of your symptoms, magnesium supplements are also generally quite safe and effective. (But, it is always a good idea to check with your doctor or dietitian before you start a new supplement.) Your healthcare provider can check the magnesium levels in your blood, but those levels might not be very useful. The amount of magnesium in your red blood cells (RBC Magnesium) might be a better test. But even then, the level of magnesium in your brain is what's most important for mental health. Low magnesium in the brain is associated with depression and neuroinflammation. How might magnesium supplements help? Increasing magnesium intake and/or supplementing with magnesium might help with:

What type of magnesium supplement is best? There are lots of different options for magnesium supplementation. Depending on what symptoms you're looking to treat with magnesium, the optimal choice of supplement will vary. If you are frequently constipated, the standard formulations of magnesium will probably help with this (such as magnesium sulfate, oxide, citrate, or chloride). It's a good idea to take the supplement at night to give it time to work - and that's the best time to take it for its sleep benefits, anyway. On the other hand, magnesium glycinate and magnesium taurinate have both been used with good results in people with depression and anxiety, and seem to have fewer unwanted gastrointestinal side effects (for those who don't struggle with constipation at baseline). A newer supplement option, magnesium L-threonate, actually crosses the blood-brain barrier and boosts magnesium levels in the brain, which might make it an ideal choice to take advantage of the neurological and mental health benefits of magnesium.

If you’re interested in learning more about how to improve your mental health and gut health through the power of nutrition, contact us or schedule a virtual telehealth appointment with me!

Note: This post may contain affiliate links. I only recommend products I love! Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist with a passion for helping people improve their mental health and gut health using integrative and holistic therapies. One of the most central topics within the gut-brain axis is the vagus nerve. Here’s why you should care about your vagus nerve, how to improve vagal nerve function, and why “toning” the vagus nerve is an important part of supporting good mental health and gut health. The vagus nerve is the longest cranial nerve in the body. It travels all the way from the brainstem to wrap around and run alongside organs throughout the abdomen, including the lungs, the esophagus, the heart, the liver, the stomach, and the large and small intestines (just to name a few). It both carries signals from the brain down to the heart and the digestive organs (motor signals, telling those parts of the body what to do) and carries signals back up to the brain from those organs (sensory signals, telling the brain what’s going on in your midsection). It’s mostly in control of autonomic functions – the things your body does without you having to think about it, like pumping your heart, breathing, and digesting your food. However, stress and anxiety affect the function of the vagus nerve pretty dramatically. When you’re in fight-or-flight mode, your heart rate and breathing speed up, and digestion slows way down. This makes good sense, since when your life is in imminent danger, you want to have adequate blood flow and plenty of oxygen to fuel your muscles, and you don’t really want to be thinking about finding a restroom. But what about the chronic, constant day-to-day anxiety of our lives today? What about people with anxiety disorders? In these cases, the vagus nerve’s function is thrown off balance. As a result, our heart and lungs will spend most of their time on high alert, working too hard, and our digestive system may become sluggish, leading to things like low stomach acid, gastroparesis (slow stomach emptying), acid reflux (also known as GERD), and poor digestion. Along with anxiety, this imbalance has been linked with depression, and with gut disorders such as IBS and IBD. If you’ve struggled with chronic anxiety or an anxiety disorder, you might resonate with some of these symptoms. Perhaps your appetite tends to be poor when you are stressed, or if you try to eat you feel like the food sits in your stomach like a rock, or you develop heartburn after eating. (On the other hand, you may have had the opposite experience, where anxiety causes your appetite to increase. This tends to be more of a learned self-soothing behavior, but doesn’t rule out having some of the same side effects of decreased vagus nerve functioning noted above.) The important question, then, is: what can we do about this? You may have been told by a well-meaning doctor, psychiatrist, or loved one in the past that you need to “reduce stress” or just “stop being so anxious.” These recommendations tend to be quite unhelpful and frustrating. But there are some truly actionable ways to help close the loop of the stress cycle and harness the power of the mind-body connection to decrease anxiety. Let’s start with the breath. I mentioned that most of the functions of the vagus nerve are “autonomic” – meaning that they happen automatically without us having to think about them. This is true for digestion, certainly, and thankfully your heart keeps beating even if you’re not thinking about it. But breathing is different. It can and does happen automatically most of the time, but you also can control it, if you so choose. Take a moment right now to notice the rate of your breathing. Is it fast or slow? Are you breathing through your mouth or through your nose? Are you holding your breath? Now take a conscious, deep inhale through your nose, feeling your belly expand like a balloon as you breathe in. Count to four as you inhale; one, two, three, four. Hold it here for a count of seven; one, two, three, four, five, six, seven. And now breathe out through your mouth slowly, for a count of eight; one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. Repeat this at least four or five more times on your own, perhaps even with your eyes closed. You may notice that this is a much-needed moment of peace and stillness, and spend a few more minutes here on your own. By all means, please do. When you have finished this short breathing practice, notice what’s going on inside your body. Has your heart rate slowed? Is your breathing a little calmer than it was when you first tuned into it? Deep breathing, or diaphragmatic breathing, is one of the simplest ways to tap into and change the functioning of your vagus nerve. While I feel like this term is a bit too simplistic, some call it “resetting” your vagus nerve. Whatever you call it, doing breathing practices like this one regularly, you can actually strengthen its function, which is why this is called building “vagal tone.” This can help improve heart rate variability, the ability of your cardiovascular system to respond to increases and decreases in stress levels appropriately – speeding up and slowing down to match the needs of the moment. A lot of research is being done on VNS devices implanted to stimulate the vagus nerve for depression, PTSD, and epilepsy, among other things. However, there are some less-invasive methods you can try today. Here are some of the other practices and tools that have been touted for improving vagal tone:

So the next time you’re feeling anxious, give your vagus nerve some love! Over time, by regularly working on toning your vagus nerve, you might find it gradually get easier to move through the stressful fight-or-flight mode and get back to resting and digesting. If you’re interested in learning more about the gut-brain connection and how to improve your mental health and gut health through the power of nutrition and lifestyle, contact us or schedule a virtual telehealth appointment with Erica, a mental health dietitian! Note: This post may contain affiliate links. I only recommend products I love! Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPMental Health, Eating Disorders, and Gut Health In part 1 of this series on coffee and the brain, we discussed how daily consumption of coffee might help protect against dementia, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease. In this part we’re going to discuss how caffeine impacts mental health, including anxiety, depression, and ADHD. Our mental health not only affects how we think, but also our views on life and how we handle situations and emotions. In recent years with the COVID pandemic, there has been a sharp increase in anxiety and depression. This may be linked to the social isolation of the pandemic. Depression is characterized by low mood. It affects sleep, appetite, emotions, and can even cause physical symptoms in the body, including fatigue and headaches. On the other hand, anxiety disorders are characterized by a persistent and intense worry and fear. It can lead to social withdrawal, and includes symptoms like sweating, having trouble concentrating, constant unrest or nervousness, and an increased heart rate. Caffeine and Anxiety As previously discussed, caffeine is a stimulant that increases energy and alertness. It blocks a neurotransmitter (a chemical messenger that relays messages to the brain and body through the nervous system) called GABA. GABA plays a role in calming nerve cell activity, meaning that it helps us relax. By blocking GABA, caffeine can increase cognitive functioning, but can also increase anxiety. People with anxiety tend to have a lower tolerance to caffeine and are more sensitive to the effects. If you or someone you know has anxiety or gets anxious easily, decreasing caffeine intake can help. Similarly, with bipolar disorders, high caffeine intake can induce a manic episode. It’s recommended that those with bipolar disorder avoid consuming large amounts of caffeine. Caffeine and Depression For those with depressive disorders, studies have shown that caffeine tends to elevate mood. Since it acts as a stimulant, there’s a boost in brain functioning and energy levels. This can help with the fatigue commonly associated with depression. Even for those without a diagnosis of depressive disorder, the mood and energy boosting effects of caffeine are probably some of the main reasons its use is so common. It’s something people joke about (but are probably being serious). For instance, the “don’t talk to me until I’ve had my coffee,” or think about how coffee shops have become a hot spot for social settings. It’s easier to socialize when you have an energy- and mood-boosting drink in your hand. Studies have also shown that a moderate consumption of caffeine is associated with reduced risk of depression and suicide, as well as an elevated mood. Caffeine and ADHD ADHD is another disorder that can be impacted by caffeine intake. Symptoms include a short attention span, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. People are often unable to sit still, have difficulty concentrating, interrupt frequently, and have excessive movements. Interestingly, caffeine has been shown to help manage these ADHD symptoms by increasing focus and alertness. However, it’s important to talk with your doctor or psychiatrist before combining caffeine with other ADHD medications, and certainly do not stop taking ADHD meds without talking with your doctor first. In Practice... It's important to note the overlap between a lot of these conditions. Many people struggle with both depression and anxiety, or both ADHD and anxiety, for example. In these cases, it’s wise to be cautious about caffeine intake. When you drink coffee, how is your mood? Your sleep? Your stress levels? Your energy levels? It may be helpful to do a self-experiment, gradually decreasing your caffeine intake and then seeing how you feel without caffeine for a couple of weeks before reintroducing it and noticing the results. You might also consider other beverages besides coffee that contain a smaller, more manageable amount of caffeine, such as tea. The L-theanine in tea (and especially green tea) has a calming effect, while the relatively low caffeine content can still have a positive impact on focus and alertness. Caffeine primarily affects cognitive functioning. As we discussed earlier, it interacts with our nervous system and brain. It increases working memory, attention, alertness, reaction times, and, as we discussed today, it can improve mood. However, too much caffeine can lead to anxiety, paranoia, mood instability, and dependence on caffeine. Stopping or decreasing caffeine consumption can be challenging because of its withdrawal symptoms, like tiredness, headaches, and mood changes. Caffeine isn’t for everyone, and can intensify anxiety and bipolar disorder, but it can also help improve mood and might help manage depression and ADHD. I hope this two-part series was informational and useful. Thank you for reading! Main research article for more information: https://www.mdpi.com/851178 Chart for caffeine intake in foods/beverages: https://www.cspinet.org/caffeine-chart If you’re interested in learning more about how your dietary choices influence your mental and neurological health, reach out or schedule a virtual telehealth appointment with Erica, a mental health dietitian! Madison McGaugh with Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPMadison is a senior at Texas A&M University majoring in nutrition with a minor in psychology.  Coffee, tea, soda, and energy drinks. These are some of the everyday beverages we consume. Especially when we have long nights and early mornings, or a never-ending workday. Maybe even kids that wake you up in the middle of the night, or exams and homework that just need to get done. Sometimes we just need that boost that coffee gives us, a little pick-me-up to start the day or to just keep going. All those drinks have caffeine in them, something that most of us are very familiar with. On average, Americans consume 179 mg of caffeine a day. But what does caffeine even do? How does it impact our brain and mental health? Caffeine is a stimulant. It plays a role in reducing drowsiness (which is why the morning cup of coffee is a go-to for many people). It has also been shown to increase concentration, motor coordination, and alertness. There is also an effect on learning and memory. Depending on genetics, people react to and breakdown caffeine differently. Some people are more sensitive to caffeine, so it takes longer to metabolize and its effects will last longer. On average, caffeine will reach its peak effectiveness 30-60 minutes after consumption. Half of the caffeine consumed will break down within 2-10 hours—this wide range is a testament to how differently each person experiences caffeine! Be wary—stimulants such as caffeine can be addictive. People also build up a tolerance, so they’ll consume more and more caffeine to feel the same effects that they did before. The problem is that your body is taking in a lot more caffeine. This can lead to sleep problems, jitters, increased heart rate, and overstimulation. So, what does caffeine do to our brain? How does it impact different neurological disorders? Does it affect men and women differently in these disorders? We’re going to talk about caffeine and how it impacts our brain and mental health over two parts. In this first part, we will focus on neurological disorders. The second part will discuss caffeine’s impact on mental health. There are theories that coffee plays a protective role when it comes to some neurological diseases, including stroke, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. Looking at research studies, people who drank at least 3 cups of coffee a day had a reduced risk of stroke. With dementia, women (more so than men) had a reduced risk of developing dementia. In Parkinson’s disease, high caffeine intake has been associated with having a protective effect, including decreased rates of Parkinson’s disease in men. (In women the correlation is a lot smaller). It’s also important to note that caffeine may help reduce the risk of developing these disorders, but once the disorder is present there is not a lot of research to suggest that caffeine will reduce the severity of the disorder. What does this mean for us? More research needs to be done in further understanding and interpreting these connections. According to the USDA guidelines, the recommendation for a safe level of caffeine intake is less than 400 mg per day (or about four 8-oz cups of coffee). If you’re curious how much caffeine you are consuming every day, check out this chart with a wide variety of common food and beverages and their caffeine amount. We’ve seen that some benefits of regular caffeine intake include protection against dementia and stroke more strongly in women, and protection against Parkinson’s disease in men. Based on these research findings, caffeine intake seems to help decrease the risk of the development of neurological disorders such as dementia, stroke, and Parkinson’s disease for some people. This doesn’t mean that it is wise to drink a ton of caffeine every day, but—good news for coffee-lovers—a moderate amount daily might be helpful in maintaining good brain health. If you’re interested in finding out how caffeine impacts risk of mental health disorders, stay tuned for part 2! Main research article for more information: https://www.mdpi.com/851178 Chart for caffeine intake in foods/beverages: https://www.cspinet.org/caffeine-chart If you’re interested in learning more about how your dietary choices influence your mental and neurological health, reach out or schedule a virtual telehealth appointment with Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCP. She specializes in nutrition for mental and cognitive health. Madison McGaughMadison is a senior at Texas A&M University majoring in nutrition with a minor in psychology. You know how kids get hyped up on sugar and then crash? Boy, aren’t you so glad that all of us grow out of that when we grow up? Yes, that’s tongue-in-cheek. We might get better at managing our moods as we get older, and our emotions and energy levels are a bit more within our scope of control. This allows us to keep focused at work even when we’re hungry and eat an ice cream cone and not run around the living room yelling at the top of our lungs. But truth be told, the same metabolic processes are still going on in our bodies, the same changes in our blood sugar, the same changes in energy level coursing throughout our muscles and brains. Just because we’re better at appearing stable doesn’t mean things are actually stable inside. For example, have you ever seen the study that looked at the differences in decisions Israeli judges passed on similar cases, merely based on whether the hearing was held before or after their morning snack or lunch break? Even the best and most well-trained of us still get hangry. Let’s say you get up in the morning and you’re in a rush. You pour yourself a cup of coffee with sugar and French vanilla creamer and head out. By the time you get to work, the coffee is gone, and your hunger is staved off for a while. But 10AM hits and you start to feel fatigued and restless again. You go for a second cup of coffee from the communal coffee pot, and grab a donut from the box someone brought in. For lunch, you stop by the local sandwich shop to get a hoagie, some chips, and a soda. After lunch, you’re feeling pretty good and really getting stuff done, until about 2:30PM when the afternoon slump begins. You peruse the vending machine in the hall and grab a candy bar (just for today, because that big deadline is coming up and you need to be productive). By the time you get finished with your work, it’s 6PM and you’re exhausted. You finally head home, ready to crash, only to find the house is a mess and no one has thought about dinner. You’re irritated and snappish. You head to the freezer, find a couple of frozen pizzas to throw in the oven, and snack on some corn chips while you wait for it to heat up. After the kids go to bed, it’s a glass of port wine, a big bowl of ice cream, and some TV to help you wind down. Then, around 11PM, you head to bed for some poor-quality sleep, only to wake up and do it again the next day. Look, work and family life are tough enough on their own. You don’t need your diet to just be making things more difficult for you to handle. Between meals or snacks when you’re feeling sluggish, hangry, irritated, and bummed out, it’s very possible that your mood is low because your blood sugar is low. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the low blood sugars tend to trigger us to crave sugar, in the body’s attempt to fix the problem. Once we’ve eaten something sweet, our blood sugar spikes and we feel much better – usually. But for some people, elevated blood sugar can feel more like anxiety or just the uncomfortable sensation of feeling “wired.” So what do we do to stop this vicious cycle? Obviously, the Standard American Diet (nicknamed the “SAD” diet for good reason) isn’t doing us much good with an average added sugar intake of 17 teaspoons per day, most of it from ultra-processed food. Cutting back on the added sugar in your diet is the simplest and, honestly, the most important step in breaking the hangry-anxious-hangry cycle. Consider all the sources – even the “healthier” choices like honey, maple syrup. Consider artificial sweeteners, as well, as they can trick your body’s hormones into spiking (like insulin, the hormone that brings sugar from the bloodstream into your cells where it can be used as energy) – and so they might cause some of the same symptoms, even without the calories or actual sugar content. Once you’ve done that, if you’re still feeling some symptoms, it might be time to consider balancing the nutrients in your meals and snacks, and decreasing the glycemic load of your meals and snacks. By “balance,” I mean trying to eat foods or combinations of foods that have a variety of nutrients. For example, I really like my clients to eat protein and fiber pairings for snacks, as these combinations are very satisfying, slow-digesting, and provide a longer-term source of energy (and thus a more stable mood). Some common examples of this might be plain Greek yogurt with blueberries, cucumbers with hummus, a boiled egg and a sliced kiwi, or carrot sticks with almond butter. Glycemic index (GI) is a measurement that ranks foods from 0-100 based on their impact on blood sugar, with pure glucose being 100. This can be very useful information to know if you’re trying to keep your blood sugar from spiking, but it’s only really useful in combination with the glycemic load (GL), which takes into account the amount of carbs per serving of the food. For example, watermelon and cantaloupe are technically high-GI foods, but since their digestible carb content per serving is relatively low, their GL is considered low. Your blood sugar probably won’t spike much after eating a serving of melon. In general, eating a lower-glycemic load diet follows pretty well along with our general idea of what a healthy diet looks like. Foods that have lower glycemic load will usually be the foods that are:

If you’re interested in learning more about how a healthy diet can boost your mood, reach out or schedule an appointment! I provide virtual telehealth nutrition care services in Colorado, California, Texas, Oklahoma, Indiana, Michigan, Virginia, Arizona, Alaska, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Washington, and Oregon, and I’d love to work with you! Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPMental Health, Eating Disorders, and Gut Health Functional Dietitian Nutritionist  Autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, is a neurodevelopmental disorder that leads to challenges with social interactions and communication, as well as repetitive behaviors. While these are the three core symptoms that lead to the diagnosis of ASD in children, there is also a very strong association between autism and gut symptoms (especially diarrhea, constipation, and acid reflux, or heartburn). More and better research studies are still needed to tease out the impact of diet on autism, and what gut symptoms are related to the disease itself versus the dietary patterns and preferences of people with ASD. However, there has already been some fascinating research on ASD and the gut microbiota, as well as the potential impact of dietary changes on neurological symptoms. Autism and the Microbiome Altered levels of gut bacteria have been strongly associated with ASD. The average healthy child’s microbiome becomes fairly diverse as they eat an increasing variety of solid foods. However, kids with autism tend to have a much less diverse diet, which seems to lead to a sub-optimal gut microbiome. Though actual gut microbiome composition varies widely, some bacterial families, like Clostridium (known for C. difficile, a common gut infection, but actually a common and generally harmless bacterial family in the gut), Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria tend to be increased in kids with ASD. The types of bacteria of which these kids have an abundance seem to produce too much of a type of short-chain fatty acid called propionic acid, and they have less of the beneficial bacteria that produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid with lots of positive effects on mental health and inflammation. There are a few case reports of treatments with antibiotics have sometimes helped to reduce anxiety and improve some behavioral measures in kids with autism, which is another fascinating sign that the gut microbiome is involved in their neurological symptoms. However, treatment with antibiotics is (and should only be) short-term – and even short-term use can have negative consequences – so this seems unlikely to become a universal solution. But probiotics and prebiotics – essentially live bacteria and their food – have a strong potential as a much safer treatment with far fewer side effects or risks. Prebiotics and Probiotics For example, a study combining an autism exclusion diet with the prebiotic supplement GOS, a type of prebiotic fiber found in dairy products, beans, and root vegetables, found significant improvements in abdominal pain and bowel habits with the exclusion diet, and additional improvements in anti-social behavior with 6 weeks of supplementation with GOS. Other studies have looked at a variety of probiotics, including single, highly specialized strains such as L. Plantarum WCSF1, or broad-spectrum probiotic supplements containing multiple different strains (mostly in the Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus families). While a person with ASD may see benefits from a standard probiotic, strains and combinations of strains specifically studied for the particular condition you’re looking to treat are much more likely to be effective. Some significant improvements in both gut health and behavioral symptoms were seen with the probiotic blend delPRO in one study (though the study did not have a control group with which to compare the experimental group’s results) and with a blend of L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, and B. longum in a different study. Restrictive and Elimination Diets Lots of different restrictive diets have been proposed for people with autism, and in some cases they may be very helpful. Artificial colors have been linked to behavior disturbances in kids, and there are also concerns about contamination with toxins and heavy metals (though the FDA does require that all artificial colors be tested for lead, mercury, and arsenic). Gluten-free and casein-free diets are commonly tried. While there are theories about how and why they work, there isn’t enough evidence to say whether they’re generally useful for people with ASD. Proponents feel that the studies that have been done on the GF-CF diet are too short-term to show much impact. Some people with ASD may have other issues with gluten- and casein-containing foods, such as lactose intolerance, Celiac disease, or non-Celiac wheat sensitivity contributing to their GI symptoms. Others may have IBS, and may see improvements from a low-FODMAP diet (always followed by a re-introduction phase). However, the more complex the diet, and the more difficult it is for the whole family to follow, the less likely it is to be feasible. Plus, for those with texture issues or those who have more difficulty eating enough variety as it is, it can be difficult to plan a diet that will give enough nutrition to meet their needs. It’s always a good idea to seek the guidance of your pediatrician, neurologist, or dietitian to discuss the pros and cons of restrictive and elimination-style diets, and how to plan them in a way that makes them nutritionally adequate and feasible for the whole family. Adding to the Diet Instead of Taking Away? For people with ASD, the diet is often already quite restricted based on personal preferences and aversions. Difficulties with food based on texture, color, and taste are common. Kids may also recognize that certain foods cause tummy pain, and refuse to eat these foods, even if they can’t verbalize this. It’s important not to make mealtime a fight. Try to stay calm and don’t allow a power struggle to arise over certain foods. We all deserve the right to choose what foods to eat and what foods not to eat, and a person with autism is no exception. However, it may be helpful to try new foods in combination (such as finely chopped mushrooms sautéed and added to spaghetti sauce) or in different forms to make the texture easier to tolerate (such as peeled and crushed tomatoes in a salsa). As much as possible, involve your child in the food preparation, and try to make it fun. Get your hands dirty together and allow your kids to acclimate to new foods outside of mealtimes to help decrease anxiety during mealtimes. Very often, it’s more about what we add to the diet than what we take away. Eating more fruits, vegetables, beans and legumes, and whole grains can increase intake of those healthy, gut-nourishing prebiotic fibers that can then feed the gut microbiome, promote more butyrate production, and improve bowel health and GI symptoms. Eating fermented foods when possible, such as yogurt with live and active cultures, can introduce probiotic “travelers” which can have a positive impact on the gut microbiome, as well. Eating a greater variety of foods makes it more likely that the diet will have enough protein, vitamins, minerals, essential fats, and polyphenols to promote a healthy brain, gut, skin, immune system, etc. And besides all that, focusing on food as the hero rather than the enemy can help to foster a healthier relationship with food, less fear of food, and possibly even less reactivity to it. We are all heavily influenced by our expectations, and people with autism are no exception to this, either. Take-aways The subject of neurological and developmental disorders and diet is a hotly debated topic, and one that is quite difficult to study. It’s also essential that it be individualized to the needs of the person with autism and their community or family. If you’re interested in developing a supportive relationship with a dietitian who can assist with making some of these difficult decisions in a non-judgmental environment, and with helping make some of these recommendations more feasible for your family, please reach out to me or schedule an appointment. I provide virtual nutrition care services to caregivers and parents living with people with autism, as well as directly to adults with ASD, throughout Colorado, California, Michigan, Arizona, Alaska, and Virginia. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPMental Health, Eating Disorders, and Gut Health Functional Dietitian Nutritionist  IBS is incredibly common in the US – somewhere between 10-20% of people suffer from it. But it’s incredibly more common in people with mood and anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, major depression, and panic disorder. Let’s be clear: IBS is not always IBS. Sometimes there are other issues going on that medical professionals can miss, especially since IBS is often a “diagnosis of exclusion” (meaning, “we’ve ruled out everything else we can think of, so it must be IBS”). It’s always important to see a provider with a specialty in gut disorders to make sure that you get the correct diagnosis. But let’s assume that the diagnosis is correct. What is going on in the gut that makes things so wonky in the brain? Or what’s going on in the brain that makes things so wonky in the gut? Since the connection between the gut and the brain goes both ways (primarily via the vagus nerve, hormones, and the immune system), problems with either one can affect the other. And that means that there is a long list of factors that can impact the gut-brain axis and trigger mood disturbances, anxiety disorders, and IBS. Dietary changes are often needed to calm an “irritated” gut, improve the composition and health of the gut microbiome, heal an intestinal barrier that has become too permeable (or “leaky”), provide adequate vitamins and minerals and amino acids to produce neurotransmitters necessary for mood stability, and more. Dietary changes sometimes include increasing fiber intake, eating more probiotic foods, eating a greater variety of foods, or, on the other hand, restricting certain foods that are common triggers (and then re-introducing them in a planned and careful way). Lifestyle changes are often needed to calm an over-worked or over-stressed mind. We all have stress, and stress is not inherently bad or harmful, but often can be when we are dealing with it in an unhealthy way or when the stress is chronic and when we aren’t good at resting and relaxing in a healing way. CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) has been helpful for many people with IBS, which is testament to the importance of managing this disorder from both a gut and a brain perspective. Yoga, stretching, and other forms of gentle movement are also helpful for some people. Probiotic supplements, fiber supplements, and herbal supplements such as natural anti-microbials, demulcents, digestive bitters, and peppermint can be helpful for some people, but I would always recommend getting advice from a trained professional such as a gastroenterologist or dietitian before starting such supplements, as they need to be carefully selected and tailored to your needs. Managing disorders of the gut-brain axis, like IBS, can be very challenging. You don’t have to go it alone. If you’re interested in working with a gut health dietitian, schedule a virtual telehealth nutritionist appointment with me or send me a message today. PS - I was recently interviewed about this topic for DeliveryRank. You can read the interview here. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist After several months of trying to work fulltime and see patients on the side in my private practice, I'm excited to share that I'm finally jumping in for "real" with many more bookable hours and lots more energy to put into sharing my passion with all of you through blogs and other resources. Have you dealt with mental health or digestive issues for months or years without finding successful treatments? Are you seeking to manage mental health symptoms with fewer medications? Do you deal with disordered eating or a relationship with food that you wish you could improve? Has your diet been gradually becoming more and more restrictive over the years because of gut health issues like IBS or IBD and you're starting to feel like food is the enemy? Please don't just keep dealing with these issues alone. Your struggles are real, and I'm here to listen and help. It's what I do, and what I love to do. Please reach out to me or book a virtual dietitian appointment with me if you're interested in finding out more about what we can accomplish together. I work with clients in many states across the US via telehealth, including Colorado, California, Texas, Oklahoma, Indiana, Michigan, Virginia, Arizona, Alaska, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Washington, and Oregon, and I'd love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist  Move over smoothies, this is my new favorite way to eat kefir. I preach about fermented foods all the time, but I know it can sometimes be hard to find practical ways to fit them into your day. I home-make my own kefir (not as hard as it sounds), so I always have lots on hand and I love to experiment with new ways to eat and love it. This one is too good not to share! So here you go, friends. Enjoy! Ingredients:

Instructions:

Variations:

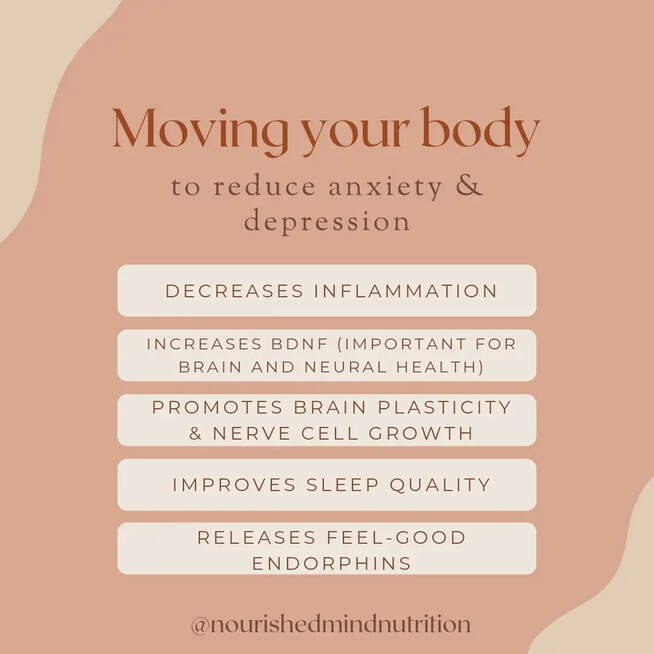

***Note: If you're wondering, "What's the deal with kefir anyway?" --let me tell you about it. Kefir is an amazing source of probiotics that, like yogurt, has been around for a very, very long time. It's sometimes called the "champagne of dairy" because of the bubbly, drinkable texture. It's a great source of Lactobacillus bacteria, which are one of the best-studied probiotics for gut health and mental health, as well as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is a probiotic yeast. Kefir has been shown in some studies to have benefits such as reducing constipation, reducing bloating, and improving mood--just to name a few. Got a favorite way to eat or drink your kefir? Share it with us below! Interested in scheduling an appointment with a gut health dietitian? I'm a virtual telehealth dietitian, and I love to make my clients amazing meal plans with recipes like this one! Reach out to me or schedule a 15-minute discovery call to learn more. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist If you've ever tried mindful eating, you know it's much harder than it sounds. It's easy to get sucked into checking your phone or turning on the TV if you're eating alone. If you're eating with others, it's easy to stop paying attention to the food you're eating. Every meal and snack doesn't have to be 100% focused. Start with just one occasion per day. Remember that anything else you try to do at the same time as eating will usually steal your focus. We're really good at eating - we've been doing it our entire lives - so we can do it on auto-pilot, and our attention naturally goes to any other activity that we're try to multi-task with. Notice your hunger at the beginning of the meal and periodically as you eat. Observe all 5 senses - eating is one of the few activities that uses all of our senses, and I think that might be part of why we enjoy it so much. Put down your fork between bites. Savor. Smile. 🙂 How does eating mindful make you feel? Is it stressful? Does it make you feel unproductive, or bored? The way you feel when you eat mindfully tells you a lot about your relationship with food, and what work you might need to do to improve it. One of my clients calls me her "food therapist." I love that. We all have a relationship with food - but is the relationship nourishing us, or is it harming us? Eating more mindfully is the first step in uncovering what that relationship looks like - and what it COULD look like. Want to learn more? Comment below or send me a message. If you'd like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me. I'd love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist  What does it mean to you to have a healthy relationship with food?🍽 Some might say it just means you "eat to live instead of live to eat" - but is that really all that eating is about? 🤔 👉What would it look like for you to have a healthier relationship with food? Would it mean spending more time thinking about food, or less? More time eating, or less? Perhaps making eating more about eating, and living life more about living life? 👉Where do you want to spend the energy you get from your food? 👉How do you want the food you eat to make you feel, both physically and mentally/emotionally? 👉How can you use food as a tool to help you feel the way you want to feel, without using it as a weapon of shame and guilt to try to force yourself into eating what you think you "should" be eating? Interested in support with building a healthier relationship with food? Message me directly or schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call! I’d love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCP@nourishedmindnutrition  I call it "slow food." In our busy culture, it can be challenging to find the time and energy to be involved in the preparation of our food. Fermented foods are one example of this. Kefir and lacto-fermented veggies are what I've got going on my kitchen counter today! We know fermented foods are amazing for us and there is tons of evidence to support their role in improving gut health, mental health, and even longevity. It's totally ok to buy these things from the store, but the benefits of doing it yourself are huge and go way beyond the superior microbial content that you get from doing it in your own kitchen. It's all about rebuilding that connection between ourselves and our food. As a mental health and gut health dietitian, I truly believe this: the more involved you are in growing and preparing the food you eat, the better your food will make you feel. The nutrients and probiotics in "slow food" are nourishing and healing. So is the process. Want to learn more? If you have any questions, feel free to comment below or message me directly. If you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule a virtual appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me! I’d love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPRegistered Dietitian Nutritionist  For mild to moderate depression, studies show that moving your body can be AS GOOD AS an anti-depressant. For severe depression, it is a an amazing adjunctive therapy. Studies have been done with lots of different types of movement, and the best thing seems to be the thing you enjoy - the thing you can stick to. ⚽️🧗♀️⚾️🏊♀️👨🦽🏈💃🎳⛸🎿🥋🚴♂️🏋♂️⛹🚣♂️ A variety of different types of movement can be wonderful, too, for your overall health. Multiple different brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate, the corpus callosum, the cingulum, and the hippocampus are often smaller in people with major depression. But guess what?! Exercise has been shown to boost brain plasticity and increase BDNF levels, a brain chemical that encourages neural growth in these very areas. 🧠💪 And did you know that just 20 minutes of movement RIGHT NOW could impact your mood almost immediately? It's hard to find anything that is that effective that quickly. 🙌 Want to learn more? If you have any questions, feel free to comment below or message me directly. If you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me! I’d love to work with you. Sources: PMID 29122145, PMID 31389872 Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCP@nourishedmindnutrition  It's one of the most common refrains from anyone in the field of nutrition and wellness: "Eat more whole foods." But what exactly counts as a "whole food"? It's a fair question. And one person's definition of a whole food may be different from the next person's. And I think it's important to say at the outset that just because something isn't a whole food doesn't mean it can't still have some health benefits. But let's talk first about what we can all agree that a whole food isn't. Whole foods are not the highly processed foods that make up most of packages lining the aisles of the grocery store. They are not the foods with lots of ingredients, most of them unpronounceable. The category of whole foods doesn't even include some of the foods that carry health halos today, like gluten-free baked goods or cauliflower pizza crust or organic granola or keto protein bars. However, being processed isn't always a sign that a food isn't a whole food. Washing and chopping and bagging kale is technically processing kale. Canned sardines, shelled pecans, frozen berries, milled flour - all are processed, but all are still whole foods. It's less a question of whether or not the food is processed, and more a question of whether the plant or animal part that the food was made from is recognizable. (I often use Cheetos as an example of this. I remember wondering what on earth they were until I finally looked at an ingredient label while studying nutrition in college. They bear absolutely no resemblance in either appearance or flavor to corn.) A whole food also has all of the components that make the plant or animal itself nutritious. For example, whole grains keep their husk and germ. Oranges keep their fiber. Potatoes keep their skins. Milk keeps its fat. (Foods lose a lot of their nutritional value when we process them too much - especially the fiber, phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals.) A whole food also ideally doesn't have added ingredients that aren't naturally present in the food, such as stabilizers, colorings, flavorings, gums, etc. Some additives aren't harmful and can actually increase the nutrient-density of the food- such as adding vitamin D to milk or mixed tocopherols (vitamin E) to oils - but I think we can all agree that we want less added sugar, salt, artificial colors and flavors, and gums in our foods. Next time you're at the grocery store, try spending a few extra minutes in the produce section. (It's the section of the store that's the most packed with whole food options!) Wherever you have a choice between a whole grain product or a refined grain product, choose the whole. Opt for foods that are less-processed, recognizable for the ingredients they contain, and nutrient-dense. If you can plant a garden, plant fruits, vegetables, and herbs that grow well in your area. When you do buy things that are processed in some way or contain multiple ingredients, think about what has been done to the food and whether it's something you could do at home in your kitchen. If so, it's most likely a whole food as well. A few examples of foods that are less-processed and more nutrient-dense:

You get the idea. As always, there's a balance here. There's no benefit to you if you're fearful or anxious about eating processed foods. You don't win any prizes for eating 100% whole foods, and trying to do better at choosing more nutritious foods is not the same as creating "food rules" about what you can and can't eat. You don't have to label yourself as being on a "whole foods diet" or make yourself feel guilty every time you eat something that is highly processed. It's about eating well, enjoying and being grateful for your food, doing more in the kitchen when you can, eating more plants, listening to your body, being compassionate to yourself and others, and using food as a tool to improve your health rather than as an implement of punishment or guilt. Want to learn more? If you have any questions, feel free to comment below or message me directly. If you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me! I’d love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCP@nourishedmindnutrition  If you’ve ever wondered, “Should I take a supplement for this?” this is the post for you. We’ll walk through a decision-making tool to help you figure out when you should take a vitamin/mineral supplement, and when you probably shouldn’t (or simply don't need to). Let’s note up front that I’ll be speaking generally in this post, because there’s no way we could cover everything in one blog. I’m also specifically talking about vitamin and mineral supplements here; some of this can be generalized to other categories of supplements, but not all of it. And as always, I highly recommend talking to a doctor or dietitian about your specific history and concerns! So – when should I take a supplement?

There’s a growing body of evidence that people with mental health issues specifically may have higher needs for various nutrients. As one small example, there are some connections between genetic B vitamin processing disorders and mood disorders, which means that some people with depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia may need more or different forms of various B vitamins to meet their individual needs.

Often, when someone’s labs show a less-than-optimal level of a vitamin or mineral and they have substantial dietary changes to make, I’ll recommend a supplement temporarily and continue to monitor their intake of that nutrient until I feel they’ve reached a point where they are consistently getting enough from their diet alone.

OK then, so when shouldn’t I take a supplement?

In general (with some notable exceptions), the nutrients we make into supplements are contained in foods we could be and should be eating. And typically, the packaging of those nutrients within a food are more “friendly” to our bodies because:

I think there’s also an argument to be made that we just don’t know all the nutrients that are out there yet! We are constantly discovering new phytochemicals and nutraceuticals that turn out to be incredibly important for optimal health and disease prevention. We certainly don’t want to miss out on these nutrients by thinking that we can just take supplements and then we don’t have to eat our fruits and veggies. The bottom line: The main questions when deciding whether to take a supplement are:

Interested to learn more? If you have any questions, feel free to comment below or message me directly. If you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me! I’d love to work with you. Erica Golden, RDN, LD, IFNCPMental health, gut health, and eating disorder dietitian  In the realm of nutritional psychiatry, some of the best evidence is for the ability of omega-3 fatty acids, and specifically fish oil (which contains fatty acids called EPA and DHA, among others) to help treat depression. So what exactly is the evidence, and what do we do with it? To start, let’s first define what we mean by fish oil. Out of all the different types of fats and oils, there are just a couple that are considered essential for our bodies – meaning that we can’t make them on our own. One of those essential fatty acids is ALA, or alpha linolenic acid, an omega-3 fatty acid. (The other is LA, or linoleic acid, an omega-6 fatty acid.) ALA is considered essential because it is the precursor to two very important fatty acids: DHA and EPA. However, a relatively small percentage of ALA is actually converted to either of these in most people. So while we can certainly eat flax seed, chia seeds, and walnuts and get a fair amount of ALA from these foods, the most efficient way to get EPA and DHA is to eat fish, especially the cold water oily fish like salmon, sardines, anchovies, herring, and mackerel, or sea vegetables like nori (seaweed) or dulse (kelp). The average healthy person can meet their needs for EPA and DHA by eating a serving of fish twice a week (preferably fish that is responsibly sourced and low in mercury). But for some people, that may not actually be enough to meet their needs for optimal health. Some mental health conditions appear to make this list. I want to preface by saying that a fish oil supplement is not for everyone. Decisions about supplements should always be made in discussion with a doctor or dietitian, because there may be interactions with other medications or concerns about other conditions that could actually make taking some supplements dangerous. For example, fish oil can increase bleeding risk and interact with some medications, like blood thinners. There also has been some evidence that for some people and some conditions, the risks can outweigh the benefits, so a conversation with a knowledgeable professional is always a good idea. For major depressive disorder specifically, however, the evidence is mounting that routine supplementation with EPA can make a significant difference in depressive symptoms. There’s a good chance that one day soon, fish oil supplements may be standard of care either as a first-line therapy or an adjunctive treatment (meaning, alongside standard medication). The dosages looked at in most studies is around 2 grams per day (for reference, you can get about 2 grams from a 4-ounce serving of salmon). Some of the mixed results in the research seem to come from varying amounts of EPA and DHA in the supplements the studies used. For major depression, most of the evidence seems to point to either pure EPA or at least a 2:1 ratio of EPA to DHA. The link between omega-3s and depression seems to lie in the inflammatory nature of depression. Studies have shown that people with higher levels of chronic inflammation linked to depression are more likely to respond to treatment with EPA. Again, before starting any new supplement, it's always prudent to talk to a health professional familiar with your personal needs and conditions, as well as with expertise in mental health treatment. It's often a good idea to use foods first to improve your nutritional status, rather than jumping straight into supplements. You might consider starting with increasing your intake of oily fish and trying sea vegetables first. If you do decide to take a supplement, collaborate with a healthcare professional to help you make an informed decision about which supplement type and brand to take. Interested to learn more? If you have any questions, feel free to comment below or message me directly. If you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment or a free 15-minute discovery call with me! I’d love to work with you.

The pervasiveness of diet culture in the world today teaches us that we must create rigid rules around our consumption of food, and we must feel guilt and shame when we break those rules. We certainly must not allow ourselves to enjoy food (unless it checks all the boxes of what we believe counts as “healthy”). On the other hand, the intuitive eating approach tells us that for the sake of our health, we must reject all diets and the limiting food rules that cause us to distrust our bodies' innate sense of our needs. Instead, we are told to eat when, where, and we want. On the other-other hand, the mindful eating approach tells us that we must focus more on food while we eat, tune into our hunger and fullness cues and learn to truly appreciate our food for the nourishment it gives us, as well as the taste, texture, scent, etc. Yet we all know that there are some nutrients that we need more of, and some nutrients that are better for us to eat less of. We all know that some foods are filled with more of the nutrients we need more of, and those are the foods we consider "nutrient-dense," while others are just kind of empty of most of those nutrients, and others are pretty high in the nutrients we know we should be eating less of. Other foods might be processed in a way that, when eaten regularly, is known to be harmful to our health. So does being anti-diet mean that we are also anti-health? Does intuitive eating mean that we believe that we can really subsist on Oreos all day, every day if that’s what we’re craving? And where does mindful eating fit in? Is it okay to diet as long as we’re eating mindfully? Sometimes having so many different terms wrapped around a topic can create a lot of confusion. There is a lot of overlap, for example, between mindful eating and intuitive eating, and there actually can be a fair amount of overlap between mindful eating and diet culture, as well. The terms themselves can be useful to help us understand the concept, but just like labeling your diet as “plant-forward,” “vegetarian,” “vegan,” or “pescetarian,” the terms can become somewhat limiting. There are often reasons to incorporate multiple approaches and to be flexible in our lives and in our diets. It can be helpful to use terms and labels to learn about a topic or to explain it to others, but it can also be helpful to lose the terms sometimes, and just explain things as we see them. So, here’s how I see it. I believe that rigid rules and restrictions around food can be harmful to the mental and physical health of the people who believe in them (whether or not they actually adhere to them). I think these rules can damage their relationship with food, with their own bodies, and their relationships with others. I believe that good nutrition includes nourishing the body and the mind – both from a biological perspective and from an experiential and psychological one. We nourish ourselves by eating food that contains the nutrients that our bodies and brains need for good health. But we also nourish ourselves by spending time eating food with others – we build relationships through and around food and eating. We also nourish ourselves by listening to our bodies’ cues of hunger and fullness; respecting our bodies enough to give them energy and nutrients when we feel those cues of hunger and sitting back from the table to allow comfortable digestion of those nutrients when we feel that sensation of fullness. We also nourish our bodies and minds through mindful enjoyment of the experience of eating and being fully present in the moment, without the accompanying guilt and shame of over-attentiveness to food and eating that is often present when dieting. (When I first started teaching classes on mindful eating, I used to use the formula Mindfulness = Awareness – Anxiety to explain this concept.) We also nourish ourselves through the gratitude that we feel and express when we eat mindfully, as we recognize all that went into bringing our food into existence and onto our plates, and the incredible process by which our bodies will use the components of that food to rebuild, grow, and fuel the living of our lives! As Thanksgiving approaches this year, I encourage you to try to shift your focus away from “shoulds” and “shouldn’ts,” and towards gratitude for the food in front of you, the people around you, and the body that carries you through the world. What do you think about these terms and other common terms surrounding our relationships with food? Leave me a comment and let me know! And if you’d like more personalized guidance, schedule an appointment with me! I’d love to work with you. Happy Thanksgiving!